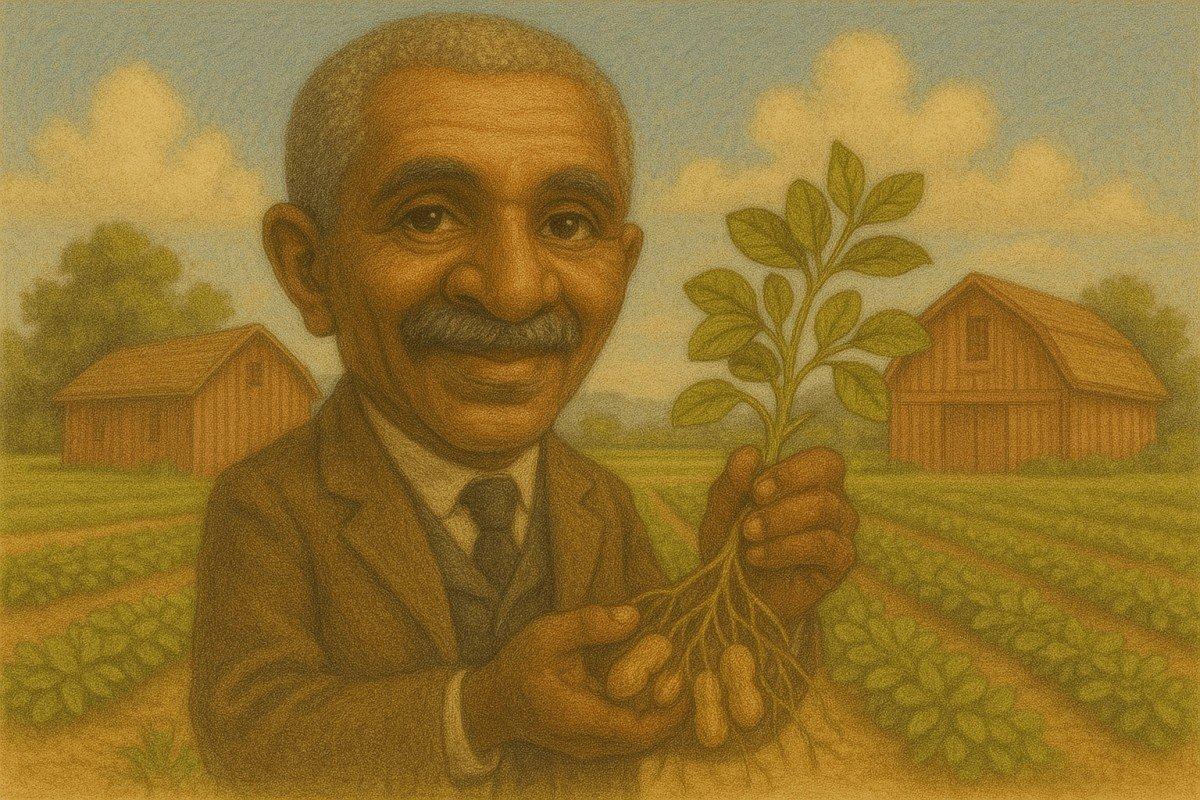

George Washington Carver: The Man Who Made Peanuts Famous (And So Much More)

Ever wonder who to thank for that delicious peanut butter sandwich you had for lunch? While George Washington Carver didn't actually invent peanut butter (surprise!), he did pretty much everything else you could imagine with the humble peanut—and transformed American agriculture in the process.

I've always been fascinated by innovators who see potential where others don't. Carver was exactly that kind of visionary. Born into slavery and rising to become one of America's most brilliant scientific minds, his story is equal parts inspiration and innovation.

From Slave to Scientific Pioneer

George Washington Carver's life began around 1864 (the exact date is unknown) in Diamond, Missouri. Born into slavery just before the practice was abolished, his early life was marked by hardship that would have crushed many spirits. Instead, it forged his resilience.

As a sickly child who couldn't work in the fields, Carver turned to plants. He became so knowledgeable about local flora that neighbors called him "the plant doctor." This wasn't just a childhood phase—it was the beginning of a lifelong passion that would change American farming forever.

After working his way through school (while simultaneously managing a laundry business—talk about multitasking!), Carver became the first Black student at Iowa State Agricultural College. By 1896, he joined Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he would spend the next four decades conducting the research that made him famous.

The Peanut Man: More Than Just a Nickname

"Hundreds of uses for peanuts? That sounds nuts!"

Sorry, couldn't resist. :) But seriously, Carver's work with peanuts was revolutionary. At a time when Southern agriculture was in crisis from soil depletion and the boll weevil's devastation of cotton crops, Carver stepped in with a solution that seemed too simple to work.

His idea? Crop rotation using peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans—plants that actually replenish soil nutrients rather than depleting them like cotton did.

But Carver didn't stop there. He knew farmers needed economic incentives to adopt these new crops. So he set out to create demand by developing hundreds of products from these plants. For peanuts alone, he created approximately 300 products, including:

• Food products like milk, flour, coffee, and various sauces

• Cosmetics including face creams and lotions

• Industrial products like insulation, wood stains, and paint

• Medical applications such as antiseptics and laxatives

One of my favorite Carver anecdotes is how he traveled the South with a mobile classroom to demonstrate his agricultural methods directly to farmers. No PowerPoint presentations or fancy tech—just hands-on education that farmers could immediately apply. That's practical genius at its finest.

Beyond Peanuts: Sweet Potatoes and Soybeans

While peanuts get most of the attention in Carver's story, his work with sweet potatoes and soybeans was equally innovative. For sweet potatoes, he developed around 118 products, including:

• Flours and meals

• Vinegar

• Starch

• Synthetic rubber

• Postage stamp glue (of all things!)

With soybeans, he created plastic-like materials, cooking oils, and even alternatives to dairy products decades before "plant-based" became a grocery store buzzword. The man was literally a century ahead of his time.

Why Carver's Work Mattered (And Still Does)

IMO, what made Carver truly remarkable wasn't just his scientific brilliance—it was his understanding of how science could solve real-world problems.

The South's economy and environment were in serious trouble in the early 20th century. Single-crop cotton farming had depleted soil nutrients, and the devastating boll weevil infestation of the 1910s and 1920s destroyed what little cotton farmers could still grow.

Carver's crop rotation system:

• Restored soil health naturally

• Diversified farmers' income sources

• Created new industries based on plant products

• Improved nutrition for rural families

Think about it—he wasn't just a scientist working in a lab. He was creating entire economic systems that lifted people out of poverty while healing the environment. In today's terms, we'd call him a sustainable development expert, an environmental scientist, and a social entrepreneur all rolled into one.

The Humble Genius

Despite his groundbreaking work, Carver remained remarkably humble. He filed just three patents, believing his discoveries were gifts from God that should be freely shared with others. When asked why he didn't patent more of his inventions, he reportedly said, "God gave them to me. How can I sell them to someone else?"

This philosophy extended to his personal life. He lived simply in a dormitory room at Tuskegee, invested his life savings in a foundation to continue his agricultural research, and focused on teaching others. In 1921, he even testified before Congress about the potential of the peanut industry, becoming the first Black man to receive such an invitation.

Carver's Legacy Today

Wondering why Carver's methods aren't more widely used in modern agriculture? Well, his approach has had more influence than you might realize.

Modern sustainable farming practices, including crop rotation, companion planting, and natural soil management, all owe a debt to Carver's pioneering work. The growing interest in plant-based products and bioplastics? Carver was exploring those possibilities a century ago.

Some of today's most innovative companies are now developing products that echo Carver's work—plant-based plastics, new applications for agricultural waste, and sustainable farming systems that work with nature rather than against it.

Final Thoughts

George Washington Carver didn't just see peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans as crops—he saw them as solutions to economic, environmental, and social problems. His ability to connect scientific innovation with practical needs made him not just a great scientist, but a true humanitarian.

Next time you enjoy anything peanut-related, take a moment to appreciate the brilliant mind that saw so much potential in this humble legume. Carver showed us that sometimes the most revolutionary ideas are also the simplest—work with nature, waste nothing, and share knowledge freely.

In a world increasingly concerned with sustainability and natural solutions, Carver's approach seems more relevant than ever. Not bad for ideas developed over a century ago by a man who began life in slavery and ended it as one of America's most respected scientists.